Latest

Insights

- Insights

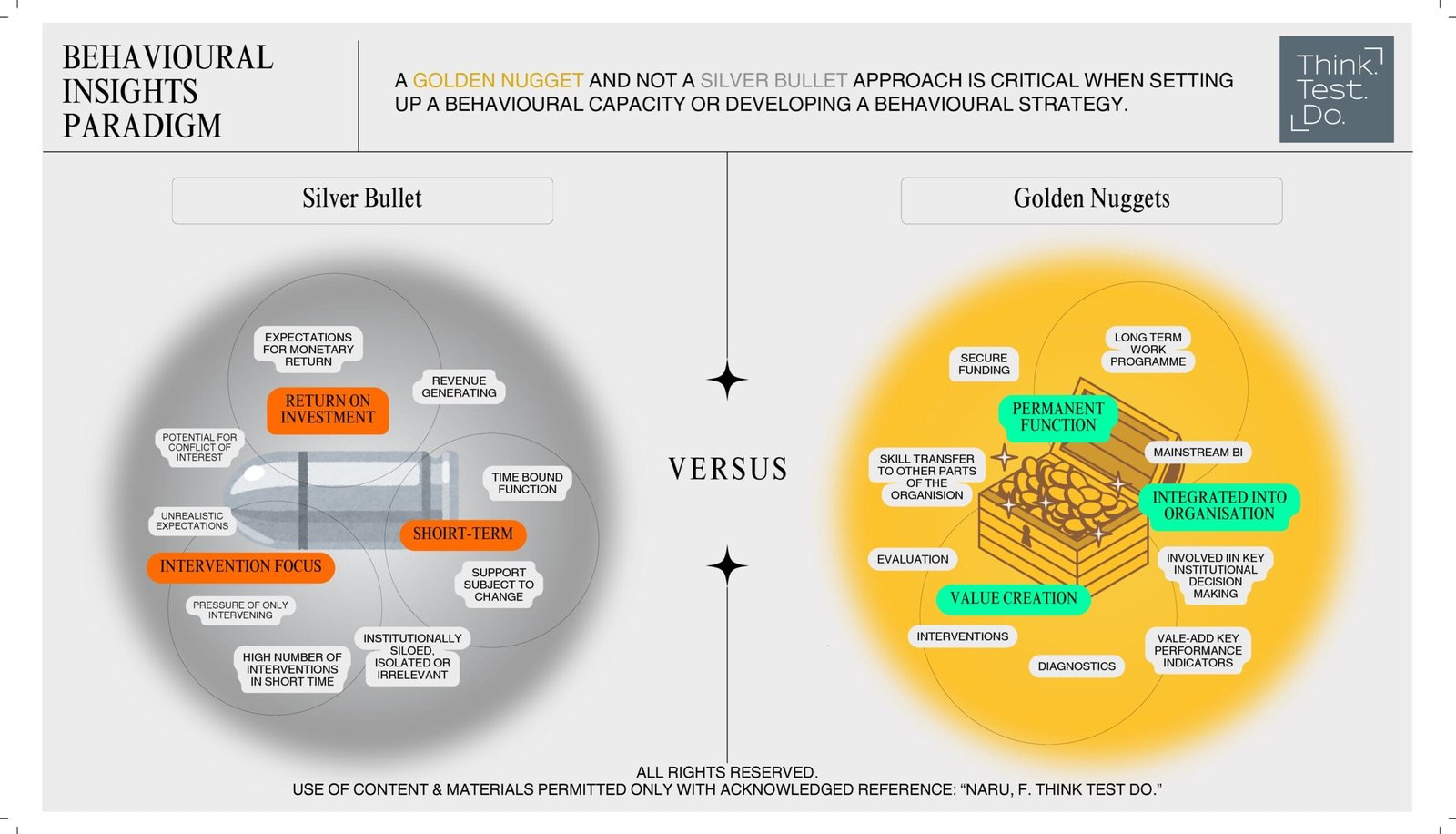

Behavioural Insights: Finding Golden Nuggets not Silver Bullets (#Teams)

The application of behavioural insights has not always been easy, with a number of countries and organisations facing challenges in when setting up and operating their behavioural insights function. While the number of behavioural public policy bodies has grown significantly over the past decade many have struggled and some have ceased to operate (Naru, F 2024).

In the field, there has been an ongoing discussion for some time on the direction and best use of behavioural science in practice (for example OECD (2017), Sunstein C. R., Reisch L. A. (2019), Nesterak, E. (2020), Chater, N. & Loewenstein, G. (2022), Hallsworth, M. (2023)). From our experience of helping to set up behavioural capacities inside institutions and advising them in how they operate, we have found that one of the key difficulties lies in the expectation to find silver bullets to problems. Behavioural science providing “silver bullets” has not been a promise made by experts, yet this misunderstanding has prevailed in the selling and understanding of behavioural science.

This silver bullet approach, usually charges the body or unit to run a high number of interventions annually, usually as the key KPI, often within a short period of time with high measurable real-world impact. They are often also set up for a short period of time within which they must “prove themselves,” beyond the number of interventions run. This may even include a requirement to demonstrate a “return on investment” either in terms of the direct financial causal impact of their interventions against the funding for staff and other operational costs. Or the amount of revenue generation from selling their capability inside or outside of their organisation.

The silver bullet approach is problematic. And costly.

These expectations become limitations. The rush to intervene compromises diagnostic work that is required to intervene effectively in the first instance. The number of interventions is often high and unrealistic for a new body in set up mode, and at least for meaningful or usable results. And the “return on investment” is a clause that is not given to other functions in the organisation that are similar (for instance how many other corporate or input functions within an organisation require a ROI?). But this ROI clause can also cause a conflict of interest for the behavioural body in its own decision-making on how to operate and function. This can lead them to operate in a silo and competing with other functions instead of working collaboratively with institutional stakeholders.

Behavioural bodies should rather have a “golden nugget” approach. That is to be in the business of creating value to the organisation using a variety of innovative and evidence-based tools, not only seeking interventions. This may include diagnostics and analysis. Or evaluations with recommendations that may not be behavioural interventions – but other solutions that will fix the problem such as structural change. This leads to greater “psychological” security for the unit with long-term funding and programming, as they are set up as a valued part of the organisation. They are also more integrated into the organisation, including the decision-making processes, and engage in skills transfer of behavioural science across their organisation.

Adopting the “golden nuggets” paradigm leverages the potential of behavioural science inside organisations and creates an environment where it can be mainstreamed sustainably. It also allows the potential to move from individual interventions toward more systemic solutions. But more broadly it becomes a recognised capacity inside organisations. This capacity may or may not be a separate entity or unit, but it is a permanent capability of an organisation. Like many other strategic parts of the organisation.

The capability to better understand human-behaviour is something that most organisations will require, now and in the future. This includes in digital transformation or in the adoption of AI. For organisations to be effective in deploying behavioural science, it will be imperative to seek golden nuggets. Silver bullets will only go so far…

*Source and Further Reading:

OECD (2017), Behavioural Insights and Public Policy: Lessons from Around the World, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264270480-en.

Sunstein, C.R., & Reisch, L.A. (2019). Trusting Nudges: Toward A Bill of Rights for Nudging (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429451645

Nesterak, E. (2020). Imagining the Next Decade of Behavioral Science. Behavioral Scientist. https://behavioralscientist.org/imagining-the-next-decade-future-of-behavioral-science/

Chater, Nick and Loewenstein, George F., The i-Frame and the s-Frame: How Focusing on Individual-Level Solutions Has Led Behavioral Public Policy Astray (March 1, 2022). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017&am, SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4046264 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4046264

Hallsworth M. A manifesto for applying behavioural science. Nat Hum Behav. 2023 Mar;7(3):310-322. doi: 10.1038/s41562-023-01555-3. Epub 2023 Mar 20. PMID: 36941468. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36941468/

Naru, F. (2024). Behavioral public policy bodies: New developments & lessons. Behavioral Science & Policy, 10(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/23794607241285614